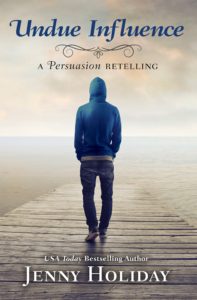

Second chances only come around once.

Eight years ago, Adam Elliot made the biggest mistake of his life. Now that mistake is coming back to haunt him. His family’s beloved vineyard has gone into foreclosure, and the new owner is the sister of the only man he’s ever loved—the man he dumped under pressure from family and friends who thought the match was beneath him.

When Freddy Wentworth, aka the bad boy of Bishop’s Glen, left town with a broken heart, he vowed never to return. But a recently widowed friend needs his help, so here he is. He’s a rich and famous celebrity chef now, though, so everyone can just eff right off.

But some things are easier said than done. Despite their attempts to resist each other, old love rekindles—and old wounds reopen. If they want to make things work the second time around, they’ll have to learn to set aside their pride—and prejudice.

Buy the e-book

Amazon | Apple Books | Barnes & Noble | Kobo

Buy the paperback

The Ripped Bodice | Love’s Sweet Arrow | Indie Bound | Amazon | Books-a-Million

Buy the downloadable audiobook

(also available in audio CD at some retailers)

Amazon | Audible | Apple Books | Kobo | Libro.fm

Chapter One

“‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that—’”

“Oh, fuck off.”

Playing dumb, Adam manufactured a confused look and aimed it at his sister. “Pardon me?” No matter that Betsy was pushing thirty, Adam still enjoyed bugging his big sister.

She rolled her eyes and waved her hands vigorously in the air in an attempt to dry her freshly painted fingernails. “You know that’s not what I meant when I asked you to read to us.”

Adam’s mother heaved a put-upon sigh. Wilhelmina Elliot, of Kellynch Vineyards in Bishop’s Glen, New York, was a woman who, unless there was a gun to her head, never read anything but Page Six. Or, in a pinch, the crime report in the Bishop’s Glen Bulletin.

Unlike her daughter, though, the Elliot matriarch would never resort to vulgar language to register her disapproval. She merely murmured, “Language,” at Betsy, then pointed a shiny purple talon—her nails were wet, too—at a stack of newspapers and magazines on the floor next to the sofa.

“You’d both like this book if you gave it a chance, I think,” Adam said even as he exchanged it for the Post. “There’s lots of conniving in it.”

“Lots of what?” Betsy blew on her fingers.

Adam tried not to roll his eyes as he shook Page Six Magazine out of the Post. Something caught in his chest to think that this might be the last time they did this. Was he going to…miss this?

No. That was crazy. He was going to miss Kellynch something fierce—losing the vineyard was going to be like losing a limb—but this weird, nineteenth-century-esque ritual in which his relatives summoned him to read to them while their nails dried was a prime example of why he’d moved out of the main house four years ago. He loved his mom and sister, and he believed they loved him, in their way. It had not been easy, getting to a place where that was true. Theirs was a hard-won affection, and easier to maintain when he could love them from afar, from his cozy, solitary motorhome among the vines at the far end of the property.

But still. Once more for posterity. He cleared his throat. “Paris Hilton’s dog died, and she’s planning a funeral with—”

“This is old news.” Betsy waved her hands again but this time in a dismissive rather than a nail-drying gesture. The fact that he could tell the difference was probably pretty pathetic.

“Well, I’m not sure print is the most efficient format for the timely delivery of gossip.” He got out his phone. “Is the Wi-Fi still on?” The electricity was, so maybe it would be. But, no. And he’d be damned if he used any of his data to read the gossip pages to his mom and sister. Like them, he was broke. Unlike them, he was not in denial about it. Tomorrow morning, he was moving his RV from the estate to his brother’s yard in town, and nothing about his modest existence would change—except of course for the fact that his heart, such as it was, would remain behind, tangled up in the vines at Kellynch.

But he was resigned. He had plenty of experience walking around with a broken heart. Freddy had made sure of that.

No, Rusty had made sure of that.

No, even that wasn’t fair. Adam had no one to blame but himself for the state of his heart.

“What I really want to know is what’s going on in the Hamptons.” Betsy slumped theatrically against the back of the sofa but kept her arms in the air so as not to mar her manicure. She looked like a zombie taking a rest.

“You’ll find out firsthand soon enough,” Adam said.

“I can’t stand that we couldn’t leave today. Tonight’s the Art Hamptons opening party, you know, and Charlie has tickets.”

He did know. She’d been talking of nothing else since it was decided that she and their mother would take a family friend up on an invitation to join him in the Hamptons for a couple weeks. Adam feared that “take Charlie up on his invitation for a couple weeks” was actually a euphemism for them having invited themselves for an indefinite stay, but honestly, he was too exhausted to care. For the most part, he’d made his peace with carrying out his duty to his family, but clearing out the house had been both physically demanding and heartbreaking, and he needed a breather from babysitting them.

Charlie had been a professional friend of Dad’s through the New York Wine & Grape Foundation. He’d been in touch after Dad’s death and had helped set them up with the ultimately unsuccessful winemaker who’d taken over—not that Adam blamed either the winemaker or Charlie. You couldn’t do something with nothing, and at the rate his family spent money after Dad’s death, what they’d had to work with was basically “nothing.”

He sort of felt like Charlie had done enough for their family, but Adam was so tired. His leg required a lot of rest at the best of times, given his dogged commitment to walking everywhere. And this was not the best of times. So he was just going to let Charlie have his mom and sister for a while.

Betsy sighed. “If only we could have left today.”

“I don’t know what to tell you,” Adam said. “Mom has to be here for the auction tomorrow.” He might do everything around here, but on paper the vineyard belonged to Wilhelmina—for one more day, anyway.

“Adam, you need your hair cut.” His mother was pretending she hadn’t heard anything. Just like she was pretending their home wasn’t going into foreclosure. Pretending she and Betsy hadn’t run the family business in to the ground. “Your features are too delicate for long hair.”

“It’s not long.” It wasn’t the short-sided fascist cut she preferred on him, and yes, maybe he was a bit overdue for a trim, but no reasonable person would call it long. But then, when had his mother ever been reasonable?

“The limp is enough, dear. You don’t need another unusual feature to draw people’s attention.”

Isn’t drawing people’s attention one of your favorite pastimes?

He kept his mouth shut, though. There was no point. He’d long since learned that he could either have a family or not have one, and if he wanted one, it came at a cost.

“Not to mention the gay thing,” his sister added.

Yes. The gay thing. Adam sighed. A shaggy-haired, gay guy with a limp: what a scandal. Thankfully, the gay thing really wasn’t a thing anymore. To his mother’s credit, after an initial freak-out, she’d gotten over his coming-out at age seventeen pretty quickly. It generally didn’t appear on her laundry list of his shortcomings—or at least very high on that list.

“Today’s Bulletin is here, isn’t it?” his mother asked, apparently having lost interest in criticizing his appearance. “You didn’t have them stop the subscription until tomorrow, right?”

“Yep.” Adam opened the local paper to the crime blotter. “Drunk and disorderly, Stone Road.”

“That’s Glen Lake Estates.” Betsy, naming another of the local vineyards, perked up.

“Officers were called to investigate a disturbance created by two men who became incensed when told a tour package they purchased did not come with unlimited refills.” Adam chuckled. “One of the individuals, upon talking to an officer, elected to upgrade to the unlimited option. The other grew increasingly belligerent and was arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct.”

His mother sniffed. “I’m not sure what they expect with those…” She wrinkled her nose. “Tours.” Bringing people in on buses like that. Honestly. I wouldn’t want a sip, much less an unlimited amount of any of Glen Lake’s so-called Riesling.”

Adam refrained from pointing out that Glen Lake, unlike Kellynch, was thriving. Those busloads of tourists his mother found so beneath her kept the place afloat. The time for those arguments was done, though. You couldn’t undo foreclosure. She’d never listened anyway, when Adam had tried to explain that from a simple accounting perspective, expenses could not exceed income indefinitely. Even he, who had never been a scholar or known much about the winemaking side of things, could understand that much.

He went back to the newspaper. “Domestic disturbance. Forty-eight-hundred block of Rook Street in Uppercross.” Betsy narrowed her eyes and pursed her lips. She was trying to figure out who it might be. “A twenty-five-year-old male summoned police to report that his estranged girlfriend threw a Bible at him.”

“Oh! That’s Henry McGuire!” Betsy exclaimed.

“It certainly is.” Wilhelmina sniffed some more. There was nothing his mother enjoyed more than subtly displaying her disapproval and therefore her superiority. “Charlotte Haywick threw a Bible at Henry McGuire? She’s in seminary—can you imagine? Acting like that when you’re supposed to be…godly?”

“It’s not really seminary,” Betsy said. “It’s some kind of weird hippie thing.”

“I think it’s just Unitarianism,” Adam said. It wasn’t like Charlotte was in some Hollywood cult, which Betsy herself had flirted with enough a few years ago that Adam had basically had to kidnap and deprogram her. But he took her point. Charlotte Haywick and Henry McGuire had a longstanding on-again, off-again relationship—they had since high school. Everyone always assumed they would end up together, but there certainly had been a lot of drama along the way. It kept the entire town riveted.

The old mantel clock chimed nine o’clock. Adam put down the newspaper. “Sorry, but I need to get this room done.”

The library was the last room left to pack up. His mom and sister, given their indifference to books, had left it to the end—or, rather, left it to Adam, as they did pretty much every unpleasant task. It was also the only room in the house that had any furniture left in it, hence their having commandeered it for foreclosure-eve manicures. Because God forbid they should be forced to vacate the home and vineyard that had been in their family for three generations without their nails done. They already thought it a terrible sacrifice that they’d had to give up their weekly mani-pedi salon appointments. It’s not extravagance, his sister had protested. It’s just the bare minimum of what’s considered socially acceptable.

A flare of anger ignited in Adam’s chest. He was pissed at his mother for letting their family’s legacy crash and burn. She took no responsibility for anything, and she never would—and she had taught her daughter the same. His younger brother, Mark, wasn’t much better, but at least he had his own house, so he wasn’t so much Adam’s problem.

When Adam’s father was alive, he’d managed to keep the family’s profligacy in check, but as hard as Adam had tried, he hadn’t been able to replicate the feat and had been forced to watch Kellynch slowly bleed out over the last several years.

But it was useless to be angry with them. Wilhelmina and Betsy were professional martyrs. He could either accept that and have a family, or fight against it and be cast out.

And Adam was nothing if not practical.

And while he had done his best to try to keep things going at Kellynch after his dad died, all his interventions had accomplished was to prolong the inevitable. Now he just wanted to be done. And this was the last task: sorting through the books.

“Are your nails dry?” he asked his mom and sister. “Why don’t you head out to your hotel, and I’ll finish up here?”

“I thought it would be best if you did this room,” his mother said. He didn’t bother pointing out that he’d done every room.

“Will you see us off in the morning?” his sister asked.

“I can’t. I have to work.” Some of us earn our living.

“Oh, Rusty will give you the morning off,” his mother said.

Adam didn’t want the morning off, was the thing. “He can’t. We have a transmission that’s giving us major problems, and the mayor needs a flat replaced before ten o’clock because he has to drive to Seneca Falls for a meeting.”

“Well.” His mother stood and brushed her hands together as she looked around the half-packed room. “I guess that’s it, then.”

“I guess it is.”

“Really, it’s for the best,” his sister said. “I never liked—”

“Text me when you arrive safely.” Adam pitched his voice to drown her out because, God help him, he only had so much patience. If his sister started up with one of her sour-grapes—no pun intended—rants about how boring and sleepy Kellynch and Bishop’s Glen were, he could no longer be responsible for his actions.

Adam loved this town. His grandmother had been one of its most prominent residents back in the day, and he couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. Yes, it was kind of dull and was slightly down-at-heels aside from the slice of it right along the lake where the wealthy residents and summer people lived, but it also had vines and forests and the big blue lake. It was home. And given that he no longer had Kellynch, at least he still had Bishop’s Glen.

Finally, following a flurry of air kisses and hands-off hugs—got to protect those nails—he was alone.

He opened a bottle of pinot noir, one of the last ones from the harvest five years ago, the last year his father had overseen things. He shouldn’t have let it age this long, but he’d been saving the last few bottles for a special occasion, and saying goodbye to Kellynch was certainly “special.”

There were no wineglasses left. His dad had kept a tray of fine crystal ones in the library, which had been his retreat, but they’d been sold off months ago. So he drank straight from the bottle, deeply, letting the herby, berry-inflected vintage slide down his throat. Drinking from the bottle suited him anyway. If there hadn’t been a vineyard in the family, Adam would have been a beer drinker, and probably a mass-produced macro-brew drinker at that. He’d never been as refined as his mother wanted. Or as ambitious as his best friend Rusty wanted. He was a guy who fixed cars by day and puttered around the vineyard by night, doing what he could to keep things in repair. Trying in vain to make his mother see that they needed to do things differently or they’d lose everything.

The wine was good. Pinot was a finicky grape for this cool-climate region, but the weather had cooperated that year, and his dad really had had the touch. His grandma had been competent as a winemaker, one of the region’s pioneers in experimenting with cold-weather varietals, but his dad had been great. He’d been trying to make Kellynch into a real player in the region, and he’d been starting to see some success—some local awards and a few new, big wholesale clients. They’d even started talking about spiffing the place up so they could open themselves up to the public for tours and tastings.

But then he up and died.

If only he had allowed Adam to help him, like Adam’s grandma had, Adam might have known enough to save things once his dad was gone. Grandma had been content to let ten-year-old Adam trail around behind her as she did the leaf thinning, making way for the sunshine to hit the clumps of fruit, but he’d been too young to really absorb anything. His dad, by contrast, had been focused on Betsy taking over as winemaker. Adam was never sure if it was because she was the oldest or because she was the not-gay one. The one without the limp. Either way, he certainly had picked wrong. Betsy had never been interested in the actual work that went on at Kellynch, merely in the spoils of that work. She would sulk when forced to participate in tasks she thought boring or menial.

By contrast, whenever Adam volunteered his services, he’d been rebuffed. The winter pruning was too delicate a job, his dad would insist. He didn’t know how he knew what temperature to ferment the Riesling at, he just knew. It wasn’t teachable. You had to have a knack.

Eventually, Adam had gotten the message and stopped offering.

He allowed himself a few more swigs of wine before replacing the cork. He wanted to keep drinking, to just leave his head tilted back and chug, but there was work to be done. He gathered old newspapers and magazines and made a pile for recycling. Then he turned his attention to the books. A fair number of them, like the Austen he’d jokingly tried to read earlier, were his. He’d never bothered moving them to the RV, figuring there was plenty of room in the big house, but now he would. The winemaking tomes that had been his grandmother’s, and then his father’s, he was less sure about. It felt like a sin to throw them away. The industry in the region was young, at least on a global scale. His grandmother had been the first winemaker at Kellynch, and he remembered her bringing these books back from trips to France, pouring over them in this very room.

Yet what good would it do to hold on to them? As of tomorrow, Kellynch Estates Winery would no longer belong to the Elliots. It remained to be seen whether the new owners would even bother trying to restore it to viability as a vineyard.

He sighed and flipped open the front cover of the book he’d been torturing his sister with. Rusty had given it to him eight years ago, just after he’d talked Adam into making the biggest mistake of his life.

He had inscribed the inside.

Austen had it wrong. There’s no such thing as too much pride—or too much prejudice. xoxo, Lady RM.

Chapter Two

We got it.

Freddy glanced at his buzzing phone, which he’d left visible next to his workstation, as he chopped fennel. He poured himself a whiskey, picked up the phone, and took both items out the back door into the alley behind the restaurant. Another text from his sister arrived before he could type a reply to the first one.

Thank you so much for helping with this.

He’d been glad to do it. Just because he personally loathed that shithole of a town didn’t mean he wasn’t happy to help his sister.

Freddy: This was a foreclosure, right?

He’d lost track of the properties his sister and her husband had considered during their search—part of his aversion to all things Bishop’s Glen, probably.

Sophie: Yep. So we got it for a steal

It was sad, really. The Finger Lakes region was home to some pretty, thriving towns. Bishop’s Glen, though, was smack dab in the middle—in what his friend and business partner Ben called “the armpit of the Finger Lakes.” Too far west for people from upstate and New York City, and too far east for people from Rochester and Buffalo, it was the kind of town where the surrounding wineries drew in buses full of Groupon-toting tourists with wine slushies.

Wine. Slushies.

He shuddered.

According to his sister, who was moving back to the region from Rochester, where she had settled with her husband, there had been a lot of foreclosures in the area. He’d told her to just buy what she wanted, no need to get him involved with a foreclosure.

Sophie: I promise we’ll pay you back.

Freddy: Soph, stop it. I have more money than I know what to do with. I’m happy to help.

Sophie: Still. Once Geordie gets his business off the ground, we are paying you back. I’m going to set up a payment plan.

Sophie’s husband had, thanks to a severe knee injury, been forced into medical retirement from the navy. He had a mind to open a business taking tourists on lake cruises, which would probably be successful. His brother-in-law was smart and a hard worker, and all those wine-slushie-guzzling tourists needed something to do when they sobered up, didn’t they?

Freddy: Whatever. The idea of you buying a place in Bishop’s Glen is payment enough. You will have gone from cleaning those places to owning one. It’s very satisfying.

It was true. He and his sister had grown up helping their single mother clean hotel rooms in that goddamn town, and now Sophie was going to own a piece of it. It was a nice bit of poetic justice. In fact, I hope you sit on your porch drinking wine and looking down your nose at those bitches who used to give you so much grief.

Sophie: Ha! I’m with you in spirit, but it’s going to be hard to action that because the house isn’t visible from the road. We actually bought an entire vineyard!

Freddy: Even better. Good for you.

Fuck all those assholes who thought he and Sophie would never amount to anything. Fuck. Them. Very. Much.

Sophie: It’s not really functional right now—there hasn’t been a harvest in several years, and the vines are all out of control, but we didn’t buy it for the vines. It has good water access and lots of outbuildings where Geordie can work on the boats. And Freddy—it’s BEAUTIFUL. I love it.

Freddy took a swig of his whiskey and smiled. His sister wasn’t vengeful like he was. She probably really did love the place. He was glad about that, but he was also tickled by the notion of one of the peasants taking over the means of production.

Maybe someday we can get it going again as a working vineyard, but for now we’re just going to get settled and get the boating business going

Honestly, Freddy would rather she let the grapes rot in place while she swanned around all day eating bonbons, but that wasn’t her.

Sophie: Will you come visit? Pretty please

She knew about his aversion to Bishop’s Glen, if not the chief reason behind it. He had half a mind to make an appearance just to freak everyone the fuck out. Yes, motherfuckers, I’m back. They’d all thought he was such a bad seed back in the day. A little drinking, some poorly done tattoos. Some sleeping around—including one time he got caught getting his dick sucked in the town square by the son of a prominent summer family. It didn’t help that he and Sophie had different fathers, neither of whom had stuck around long enough to meet their kids. His had been a migrant worker—they came in the late summer to pick the grapes—who’d left before his mom even knew she was pregnant.

These things had combined to brand Freddy the bad boy of Bishop’s Glen. All he’d wanted to do was keep his head down and work, both to help out his mom and, ultimately, as a means of propelling himself as far out of that shithole as humanly possible as soon as he could get enough money together.

But they wouldn’t let him.

What would Adam have said? Every story needs an antagonist. At the time, Freddy had laughed at that interpretation. Thought that if he was the villain of Bishop’s Glen, the Beast, then Adam was his Beauty. The only person pure of heart enough to see past the facade.

But no. He’d been wrong. He’d been so very wrong.

His phone pinged again.

Sophie: I know you have a hate-on for this place, but just THINK about coming, okay? Mom was talking about visiting later in the summer—you could fly into Rochester and drive her.

He’d be there sooner than she realized. Normally, his pride would not permit him to visit, even for his sister’s sake. He’d left after that horrible night and vowed to never look back. And he hadn’t. He’d learned from his mistake, hardened his heart, and made something of himself in spite of all those assholes. Maybe because of them.

Fuck. He could still see Adam’s face crumpling. And Freddy had felt bad for him, even though Adam had been the one doing the dumping. His guts churned. Jesus Christ. Even after all these years, the memory had the power to trigger a visceral reaction. He hated that.

He needed to get a hold of himself. Look at him: he was rich and successful. He could handle a couple weeks in Bishop’s Fucking Glen.

Freddy: You’re gonna get your wish sooner rather than later, sis. Ben will be on his way to town soon, and fuck me, but I’m going to have to come with him

Sophie: Oh, I’m a terrible person! I should have asked about that right off. How are they doing? Is she still hanging on?

Freddy: Yes, but her doctors are saying a week to ten days. He’s not taking it well. It’s not like it’s a surprise—we all knew this was coming—but he’s coming unhinged. I don’t think I can let him be alone. I’ve pretty much resigned myself to coming with him and staying a few weeks. Long enough anyway until he figures out what he wants to do. I’m getting things in order here at the restaurant for us to both be away for a stretch.

Ben was Freddy’s best friend, had been since they were kids. He was the only person—besides Adam, temporarily—who’d seen through his rough exterior. And in Ben’s case, that was because he shared it. He’d had it worse than Freddy, actually, in that he’d essentially been left to fend for himself as a kid. At least Freddy’d had his mom and Sophie.

To Freddy’s mind, there were two kinds of people in the world: people who stuck by you no matter what and people who didn’t. Ben was in the former category and, as such, had earned Freddy’s fierce loyalty.

And now Ben’s wife was dying. And after she did, he was determined to head back to the town of their youth and hole up for a while.

Which meant Freddy was, too.

In Freddy’s opinion, Ben was idealizing the place. Freddy and Ben had left Bishop’s Glen together, exchanging their dishwasher and busboy jobs for similarly shitty jobs in New York City. But the difference was that in New York, there was room to climb the ladder. Bishop’s Glen had rich people and poor people and very few people in between. You either owned a vineyard or a summer place or you worked in the service industry waiting on those people and on the tourists who came to visit the wineries.

In New York, no one knew Freddy. No one looked at him and dismissed him out of hand as a result of some kind of bullshit small-town groupthink.

The gamble had paid off. After a few years in New York, both he and Ben had worked their way into progressively more senior kitchen jobs. And when they took the big leap and opened their own place with the backing of a couple of loyal, deep-pocketed customers, they’d found success beyond their wildest dreams.

That would not have happened back in the armpit of the Finger Lakes. If he had stayed in Bishop’s Glen, Freddy would still be washing dishes.

But Ben was a nicer person than Freddy was. Where Freddy had ruthlessly cut out the cancer that was his past, Ben, even in those early, heady, New York City years, had waxed nostalgic about the town of their youth. The lake, the falling-down town square that was supposedly haunted by the ghost of its founder, the bush parties—it all seemed to have a pull on him. Once the money from their Food Network show started rolling in, Ben had bought a place on the lake. And now that his beloved wife was dying, hooked up to a state-of-the-art hospital bed in Manhattan, the only thing getting him through was the prospect of “heading home,” of sitting on the deck at the lake, staring into the sunset, and letting his grief subsume him. It was like he thought the lake had magical fucking healing powers.

Sophie: Well, I’m glad I’m back in town. I can help Ben maybe—if he wants me to. And the circumstances are terrible, but I’ll be happy to see you without having to drag my ass to NYC.

Freddy: I’ll be happy to see you, too. So what’d you buy? Does it come with a wine slushie machine?

Sophie: Kellynch Estates

Freddy’s phone and his glass of whiskey both clattered to the pavement.

Sophie had bought Kellynch?

Of course she had. Because that was just his luck. That fucking town had it in for him.

There was probably an “of all the wine joints in the world” joke to be made here, but he couldn’t fight his way through the panic that was descending to make it.

But no. No panic. He needed to tamp that shit down. He was long past expending emotional energy over the inhabitants of Kellynch. He forced himself to focus. Stooped to pick up the phone, cursing the shaking of his hands—he hated it when his body lagged behind his brain. The screen had cracked—shit. Sophie was still texting.

Sophie: Kellynch is a little ways out of town, and it was never one of the big players, so you probably don’t know it.

Oh, he knew it.

Knew exactly how far out of town it was—a thirty-five minute walk on his own, closer to fifty with Adam. Knew all the private nooks and crannies of those outbuildings his sister had been raving about. Knew how cold the water was when you dipped into the lake after dark.

Knew ways to warm up inside that lake, too.

Fuck.

No. He wasn’t letting his mind go there.

Sophie: I had only vaguely heard the name. It was owned by a family called Elliot, and I do kind of remember the Elliot siblings even though I think they were all younger than I was. Anyway, it wasn’t one of the places we used to clean. And I don’t know if there’s a slushie machine! These foreclosure auctions move fast. You just kind of have to jump without really getting a detailed look at the place. But Freddy, it’s lovely. I adore it.

He tried out the phone. It still worked despite the crack. Not unlike his heart.

Freddy: What happened to the Elliots?

He immediately regretted the question. Why ask a question when you didn’t care about the answer? Hadn’t he just reminded himself that he was done expending energy on this topic?

Sophie: I don’t really know. The last family winemaker died a few years ago. I guess they couldn’t keep it going?

The last family winemaker would have been Adam’s dad—since he never let Adam in on the business. Poor Adam, left with only his crazy mother and siblings. Even though he’d been pretty distant with Adam, his dad had always been the sane one. Relatively speaking, anyway.

But no. There was no Poor Adam. Adam didn’t need—or deserve—Freddy’s pity. Freddy ordered himself to have some fucking pride and stop thinking about Adam.

Sophie: They apparently had someone in on contract after that, but it didn’t really work out. The last harvest was several years ago now. That’s all I know, really. Somehow it ended up with them losing everything. I feel a little bad taking someone’s house under such sad circumstances.

This should be good news. The part of Freddy that was reveling in the idea of Sophie sitting on her porch and looking down her nose at all the snobs in that town should be doing a dance of joy. If there was a little bit of poetic justice in Sophie returning to Bishop’s Glen as a home- and business-owner, there was shit-ton of it in her doing so at Kellynch Estates specifically. The Elliots were getting what was coming to them.

So it was fine. He would make his visit as short as he could manage, and he’d stay with Ben. Or hell, maybe he’d stay at one of those fucking B and Bs they used to clean. As soon as he was assured that Ben was going to be okay, he’d hightail it out of there.

It’s fine, he told himself again.

He blew some dirt off his damaged phone and took a deep breath to calm his roiling guts.

It did not feel fine.

Buy the e-book

Amazon | Apple Books | Barnes & Noble | Kobo

Buy the paperback

The Ripped Bodice | Love’s Sweet Arrow | Indie Bound | Amazon | Books-a-Million

Buy the downloadable audiobook

(also available in audio CD at some retailers)

Amazon | Audible | Apple Books | Kobo | Libro.fm